Coding Education for the Development of Procedural Thinking in Elementary Students with Developmental Disabilities

This study aimed to design and tentatively implement an 8-session short-term curriculum to enable elementary school students with developmental disabilities to experience procedural thinking and develop problem-solving skills through unplugged coding activities.

Specifically, the research sought to explore the process of change in the procedural thinking of students with developmental disabilities within the context of actual classroom instruction. To achieve this, both classroom behavior observation and the Procedural Thinking Test were concurrently administered throughout the coding activities to systematically analyze the learning process and resultant changes.

I. Participants

Participants for this study consisted of five elementary school students (5th and 6th grade) with developmental disabilities, all of whom were enrolled at ‘A Special School.’

Participation in the study was conditional upon securing voluntary assent from the students, along with mandatory written informed consent obtained from their guardians and homeroom teachers.

Of the five participants (N=5), four were male and one was female. Four students were diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), and one student was diagnosed with Speech-Language Impairment (SLI). It is noteworthy that all participants had no prior experience with coding education before the commencement of this research.

Specific demographic and diagnostic details for each participant are provided in the following <Table 1>.

Table 1. Participating students Information

| Participants | Sex | Ages | Disability Rating |

| A | M | 12 | DSM-5 Level 3 |

| B | M | 12 | DSM-5 Level 3 |

| C | M | 11 | DSM-5 Level 3 |

| D | M | 10 | Mild language disorder |

| E | F | 10 | DSM-5 Level 2 |

II. Instructional Design and Implementation

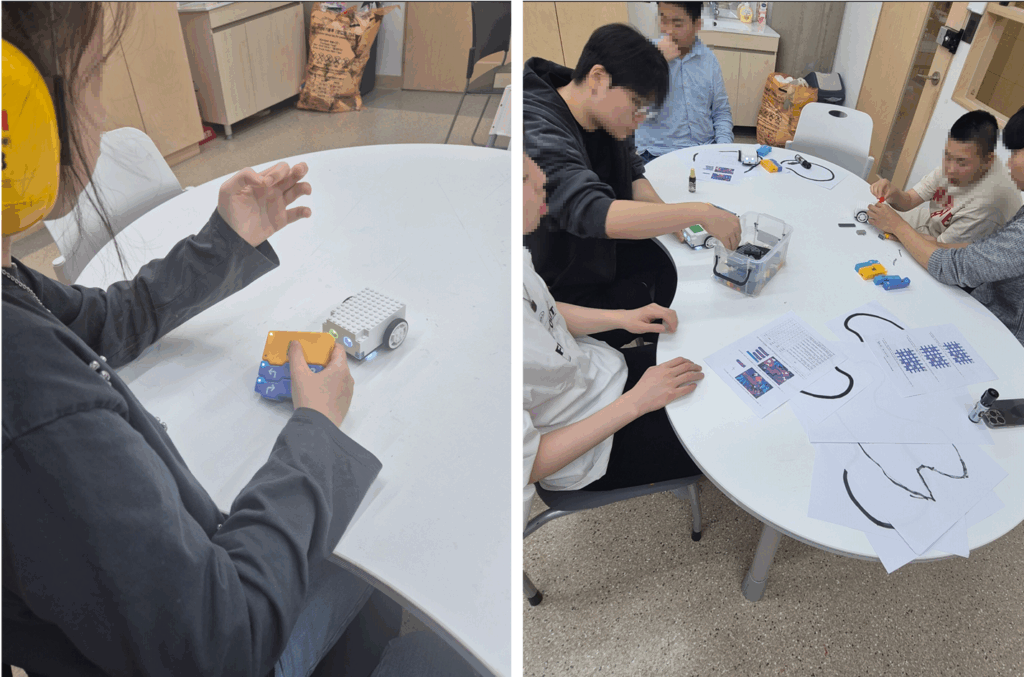

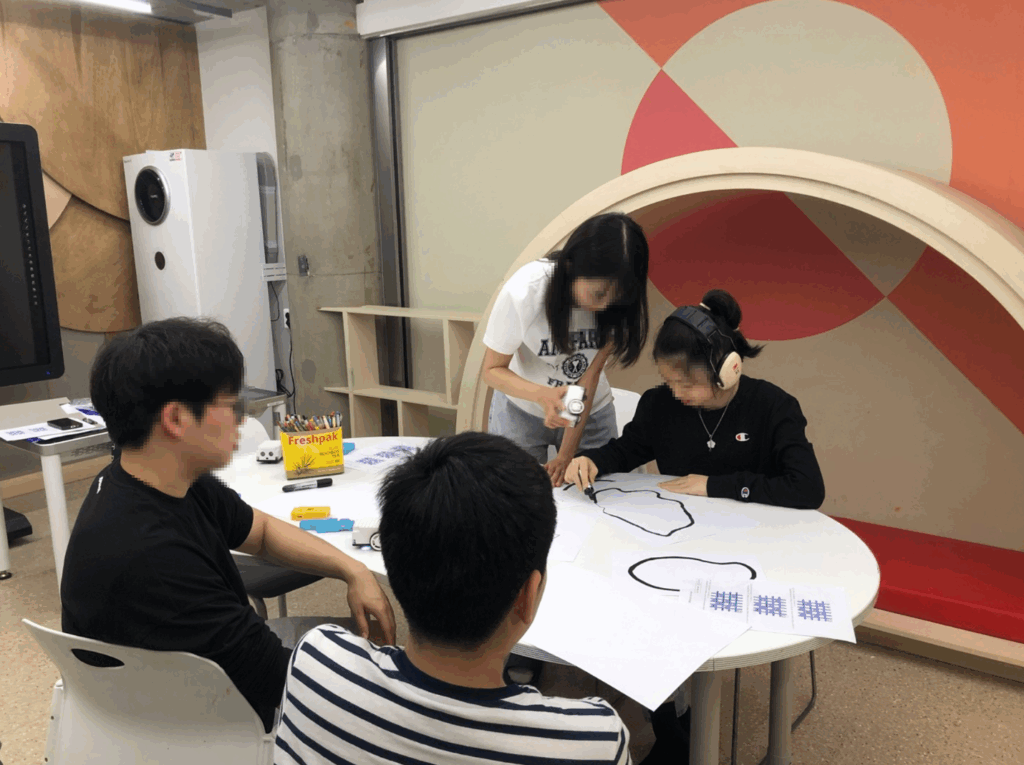

The instruction for this study utilized COBOBLOCKS, an unplugged coding tool. As a pilot study focusing on coding education for elementary school students with developmental disabilities, the curriculum was structured as a short-term program comprising eight sessions conducted over a total of four weeks. The detailed content of the lessons for each session is presented in the following <Table 2>.

Table 2. Instructional content

| Session | Content |

| 1 | Turn the robot power on and off |

| 2 | Connect and execute a single coding block |

| 3 | Change the option block of a coding block and execute |

| 4 | Understand that the outcome changes based on the option block |

| 5 | Connect and execute two coding blocks in sequence |

| 6 | Connect and execute three coding blocks in sequence |

| 7 | Change the order of coding blocks and execute |

| 8 | Understand the relationship between the order of coding blocks and the outcome |

III. Procedure and Data Collection

The instruction was carried out with dedicated one-on-one support, where one research assistant was assigned to assist each participant under the supervision of the researcher.

To assess the participants’ cognitive changes, a Procedural Thinking Test was administered both before the application of the 1st session (pre-test) and at the conclusion of the 2nd session (post-test). The Procedural Thinking Test consisted of five items, requiring participants to illustrate the necessary movements using arrows and verbally explain the steps required to travel from a starting point to a target destination.

In addition to the cognitive testing, data on the participants’ behavioral changes were collected through continuous observational recording. The researcher and the assigned research assistants systematically observed and documented the participants’ behaviors throughout the entire duration of the classes.

IV. Research Results

To analyze the findings of the study, the score trends from the five administrations of the Procedural Thinking Test (pre-test, post-test, and three sessions during instruction) were examined for each participant. Additionally, the behavioral observation records documented by the researcher and research assistants during the classes were analyzed.

The results of the Procedural Thinking Test for each participant are summarized in the following <Table 3>.

Table 3. Procedural Thinking Test Results by Participant

| Participants | Pre-test | 1-2 periods | 3-4 periods | 5-6 periods | Post-test |

| A | 0/5(0%) | 1/5(20%) | 1/5(20%) | 1/5(20%) | 2/5(40%) |

| B | 2/5(40%) | 3/5(40%) | 3/5(60%) | 3/5(60%) | 4/5(80%) |

| C | 0/5(0%) | 0/5(0%) | 1/5(20%) | 1/5(20%) | 2/5(40%) |

| D | 1/5(20%) | 2/5(40%) | 3/5(60%) | 4/5(80%) | 5/5(100%) |

| E | 2/5(40%) | 3/5(40%) | 3/5(60%) | 4/5(80%) | 5/5(100%) |

- Case Study: Analysis of Participant A’s Learning Process

Participant A understood how to turn the robot power on and off and connect and execute a single coding block during Sessions 1–2; however, the participant did not master the concept of changing the option block based on the type of command. While repeatedly performing the same coding task during the session, the participant could select the appropriate coding block, but repeated explanation was necessary after a certain period.

In Sessions 3–4, the participant was able to connect and execute two coding blocks exactly matching the provided image, including successfully changing the shape of the option blocks. However, the teacher’s assistance was still required to change the option blocks according to specific colors or sounds and execute the desired outcome. Furthermore, the participant failed to understand the resulting change in outcome based on the connection order of multiple coding blocks (sequencing).

During Sessions 5–6, which focused on motion blocks, the participant could distinguish the shapes of the blocks for moving forward, backward, right, and left, and select the desired block for execution. However, the participant could not independently connect two or more motion blocks, such as “move forward and then turn right.” With verbal assistance from the teacher, the participant was able to connect two blocks according to a sequential structure.

In Sessions 7–8, the participant was able to select the necessary blocks for problem-solving and formulate a rough solution plan. For problems involving two or three coding blocks, the participant could solve them with teacher assistance through multiple attempts of trial and error and debugging. However, spontaneous participation in coding activities was not observed throughout the program.

Table 4. Results of coding activities by session (participant A)

- Case Study: Analysis of Participant B’s Learning Process

In Sessions 1–2, Participant B successfully understood the functions of both the robot’s power button and the coding block execution button, and was able to manipulate them with appropriate force. The participant grasped the concept that the robot executes a command when a single coding block is connected to the start block and the execution button is pressed. Furthermore, Participant B recognized that changing the option block would result in diverse commands being executed. Based on this understanding, the participant was able to perform coding tasks utilizing options, such as emitting desired sounds or changing colors.

In Sessions 3–4, Participant B was able to autonomously connect and execute two to three coding blocks by reproducing the sequence demonstrated by the teacher. The participant also engaged in activities that required changing the connection order of blocks based on the teacher’s verbal instructions; however, this performance appeared to be mechanical compliance with the instructions rather than a genuine understanding of the resulting difference in outcome due to sequence change.

During Sessions 5–6, Participant B showed great interest in the motion blocks and was able to independently move the robot in the desired direction using one or two movement blocks. For a task requiring the connection of three movement blocks, the participant was able to solve the problem by performing debugging with the teacher’s verbal assistance.

In Sessions 7–8, Participant B demonstrated an understanding of the meaning of the learned coding blocks and recognized that changing the block sequence altered the command outcome. Although the participant could identify the goal state in a given problem scenario, concentration diminished, leading to a failure to comprehend problems that required four or more coding blocks.

Table 5. Results of coding activities by session (participant B)

- Case Study: Analysis of Participant C’s Learning Process

In Sessions 1–2, Participant C had difficulty distinguishing between the power button and the coding execution button when attempting to turn the robot on and off. While the participant understood the necessity of changing the option block based on the type of command, there was a tendency to primarily connect the shapes the participant personally preferred, irrespective of the problem context.

In Sessions 3–4, the participant was able to connect and execute two to three coding blocks following the teacher’s repeated instructions, but struggled to independently select the appropriate coding blocks for the problem scenario and did not grasp the concept of sequencing when connecting multiple blocks.

During Sessions 5–6, the participant could distinguish the forward/backward motion blocks and adjust the option blocks to complete simple movement coding (1–4 steps) using only the “move forward” block to reach a desired location. However, the participant experienced difficulty with pathfinding coding due to an inability to differentiate between “turn right” and “turn left.” Through repetitive learning, the participant could sequentially connect and execute two motion blocks, but this performance was challenging to sustain independently due to diminished concentration.

In Sessions 7–8, Participant C understood the meaning of each individual coding block and was able to successfully reverse the order of two blocks. However, difficulty was observed when connecting three or more blocks. Participant C consistently struggled to understand the relationship between the sequence of coding blocks and the resulting outcome, requiring continuous and significant repetition.

Table 6. Results of coding activities by session (participant C)

- Case Study: Analysis of Participant D’s Learning Process

Participant D showed high engagement with the robot during Sessions 1–2 and actively interacted with the coding robot, including independently turning the power on and off. Furthermore, the participant understood the meaning of the option blocks and skillfully changed the options to match the problem scenario.

In Sessions 3–4, the participant demonstrated a clear understanding of the concept of sequential structure by changing the order of the Sound, Dance, and Color Change blocks according to the problem scenario.

During Sessions 5–6, the participant distinguished and understood the meaning of the four motion blocks and was able to connect and execute two to three blocks. The participant also recognized that the movement path changes when the block sequence is altered, and successfully performed the activity of moving the robot to nearby locations on a given map.

In Sessions 7–8, the participant was able to perform complex pathfinding coding using five or more movement blocks, which was accomplished through debugging with the teacher’s assistance. Throughout the problem-solving process, the participant demonstrated a pattern of repetitive execution and result verification, even when the correct solution was not found immediately.

Table 7. Results of coding activities by session (participant D)

Case Study: Analysis of Participant E’s Learning Process

In Sessions 1–2, Participant E showed strong interest in the line-tracing coding block and enjoyed the activity of drawing a black line and having the robot follow it. The participant could accurately distinguish the five coding blocks learned during the session and appropriately selected the necessary blocks to solve problem scenarios. Furthermore, the participant understood that changing the option block alters the command and was able to execute code by connecting suitable option blocks for the given situation.

In Sessions 3–4, the participant was able to connect and execute two to three blocks based on the coding block patterns presented by the teacher or verbal instructions. The participant utilized the Color Change and Sound blocks to implement desired colors and sounds. Throughout this process, the participant demonstrated an understanding that the command execution order changes based on the block connection sequence.

During Sessions 5–6, Participant E distinguished and understood the meaning of the four motion blocks. The participant could independently solve problems involving two motion blocks and, with the teacher’s assistance, was able to move the robot using three motion blocks.

In Sessions 7–8, the participant could move the robot by connecting four or more motion blocks, which was accomplished through multiple debugging attempts with the teacher. Notably, the participant showed a preference for a specific problem-solving approach: when one step of “move forward” was insufficient, instead of modifying the option block of the existing block, the participant chose to solve the problem by adding a new “move forward one step” block to the sequence.

Table 8. Results of coding activities by session (participant E)

Based on the synthesis of the individual observational records, all participants demonstrated an expansion in the scope and complexity of their target behavior performance throughout the instruction period.

In particular, Participants D and E showed a progressive increase in the number of connected blocks and the complexity of the structural logic as the sessions advanced, even acquiring higher-order procedural thinking elements such as debugging. Participants A and C showed relatively moderate improvements, but they achieved stable acquisition of fundamental skills, including basic block connection and option modification.

Overall, the findings of this study suggest that even a short-term coding education program can induce positive changes in the development of procedural thinking skills among elementary school students with developmental disabilities.

V. Conclusion

This study was an exploratory pilot investigation that designed and implemented an 8-session coding education program aimed at enabling elementary school students with developmental disabilities to experience procedural thinking and cultivate problem-solving skills through unplugged coding activities. The program was specifically structured to familiarize students with procedural thinking via play-based activities, which are emphasized in the elementary level of the Special Education Curriculum, thereby laying the groundwork for expansion toward programming-based problem-solving in the secondary level.

The research results showed that all participants achieved an improvement in their post-test scores compared to pre-test scores on the Procedural Thinking Test. Notably, Participants D and E showed steady growth as the sessions progressed, and Participant B demonstrated rapid improvement after the midpoint. Conversely, Participants A and C showed more moderate increases, yet overall positive changes were confirmed.

The analysis of the in-class observational records provided the following implications:

First, elementary school students with developmental disabilities were able to form basic coding skills by understanding the meaning of fundamental command blocks and options, and executing them through coding education.

Second, participants progressively deepened their procedural thinking and logical problem-solving abilities by sequentially connecting coding blocks and repeatedly engaging in debugging activities.

Third, while some students exhibited rapid growth during the instruction, others who experienced greater difficulty showed gradual improvement through repetitive learning and feedback, suggesting that the learning effect varied somewhat depending on the severity of the developmental disability.

Although this study has limitations as an exploratory research project involving a small number of participants and a short-term program, it is significant as it confirmed that a coding education program based on the Special Education Curriculum can have a practical, positive effect on the development of procedural thinking skills in elementary school students with developmental disabilities.

References

Bocconi, S., Chioccariello, A., & Earp, J. (2018). The Nordic approach to introducing computational thinking and programming in compulsory education. Nordic@BETT2018 Steering Group. https://doi.org/10.17471/54007

European Commission. (2022). Reviewing computational thinking in compulsory education: State of play and practices from the field. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2760/07580

Elshahawy, M., Bakhaty, M., & Sharaf, N. (2020). Developing computational thinking for children with autism using a serious game. 2020 24th International Conference on Information Visualisation (IV), 761–766. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/IV51561.2020.00135

Karaman, G., & Seferoğlu, S. S. (2024). Identification of performance, motivation, and support needs in coding education provided for the students with mild intellectual disabilities. Educational Academic Research, 55, 82-92. https://doi.org/10.33418/education.1487199

Kim, M., Kim, J., & Lee, W. (2025). Intellectual disabilities and programming: Improving computational thinking-based problem solving. Education and Information Technologies, 30, 12101-12141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-13253-2

Kim, M., Kim, J., & Lee, W. (2024). Enhancing computational thinking in students with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disabilities: A robot programming approach. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2024.2394735

Taylor, M. S. (2018). Computer programming with pre-K through first-grade students with intellectual disabilities. The Journal of Special Education, 52(2), 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022466918761120